It took about a decade of concerted story telling, media strategy, tourism success and breakout artists to correct the dominant narrative about Nashville that it was, first and last, a country music town, rather than a fully rounded Music City. One thread of the effort was the story of R&B music in Nashville.

It took off thanks to Michael Gray and his colleagues at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, who assembled the long running exhibit Night Train to Nashville and two award winning companion anthology albums. Now there are new sparks on the Jefferson Street corridor, the former live music hotbed. And 2019 will see the opening of a National Museum of African American Music in the heart of downtown Nashville. Guest producers Matt Follett and Brady Watson prepared the following story, which appeared on WMOT's talk show The String.

On Nashville’s Jefferson Street today, one notices a Family Dollar store, a bail bond bus stop advertisement, a hair salon and apartment buildings. It’s hard to imagine this area used to be a national epicenter of rhythm and blues music. The Elks Lodge is where Otis Redding and Little Richard played at Club Baron in the 1960s. The rest of the clubs are all gone. But when you enter the Jefferson Street Sound, the musical past come alive as if you’re pushing play on the jukebox for that old favorite R&B song.

“Oh man the vibe was like nothing that you’ve ever seen before. It’s sort of like going to New York and going to Harlem,” says Lorenzo Washington, owner of Jefferson Street Sound. In the 1960s, he and his buddies would cruise down Jefferson Street to hit up the R&B joints. Now his music recording studio, rehearsal hall and museum bridges Jefferson Street’s present with its past.

“It was really exciting being in the clubs. When you walk in the clubs there were folks up in the floor dancing and swinging each other around on the dance floor,” Jefferson said. “And talking from table to table. Just having a good time. Just enjoying being out on a Saturday or Friday night.”

Frank Howard, the lead singer of Frank Howard and the Commanders, is one of the many local Nashville musicians who entertained lively fans. He remembered how special it was to play on Jefferson Street among other great Nashville talent.

“The New Era, we played there. All the clubs were always crowded. It was always a competition to see who had the best band in Nashville back then,” he said. “You know, Johnny Jones and the King Casuals or the band at the Stealaway or the Baron.”

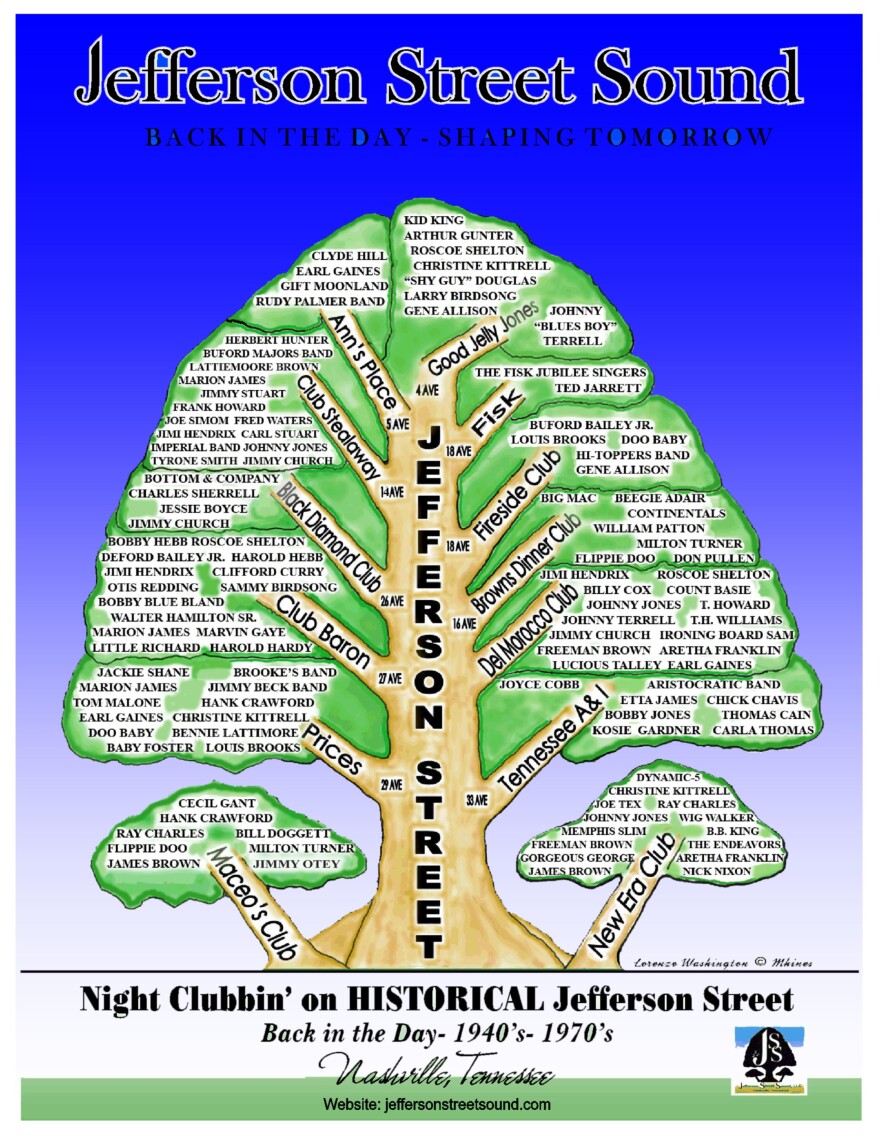

Local and nationally known performers created a special R&B atmosphere in Nashville. Washington has created a mural, Night Clubbin’ on Historical Jefferson Street, to preserve their legacy. It takes the form of a tree, with each branch represents a club with the artists that appeared there.

“That tree will always say (that) Marion James played at the Del Morocco. James Brown played at the New Era Club,” Washington said proudly. “See that tree is going to always be representative to the lifestyle that was on Jefferson Street in the 50s, 60s, and 70s.”

Jefferson Street’s music scene was muted in the 1960s. While plans to construct Interstate 40 near Vanderbilt University were proposed in the 1950s, Nashville politicians eventually approved of building highway 40 straight through the heart of Jefferson St music district.

Lorenzo Washington listed the numerous ways Jefferson Street suffered.

“Jefferson Street had over 600 homes and businesses: hotels, banks, churches, funeral homes, drugstores, grocery stores, ice cream parlors, shoe shine shops. It had all of that and more.” Washington stated. “And when the interstate came through, it corrupted all of that.”

The city branded itself as the country music capital of the world for the next three decades. But it was the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, soon after moving in 2001 from Music Row to its current location downtown location, that revived the African-American side of Music City’s story. In 2004, it debuted “Night Train to Nashville,” a long-running, groundbreaking exhibit.

Michael Gray, Museum Editor and co-curator of “Night Train to Nashville,” noted how important it was to raise awareness of the genre: “The story of Nashville’s rhythm and blues was becoming a bit of a lost history. We wanted to show the contributions that R&B musicians made to Nashville becoming Music City.”

Gray interviewed and collaborated with notable artists including Frank Howard, Johnny Jones, Earl Gaines and Ted Jarrett to tell the story of Jefferson Street and of the booming r&b radio station, WLAC.

“You cannot overstate the importance of WLAC,” Gray said. “I mean in some ways WLAC was to rhythm and blues what WSM has been for country music.”

Gray remarked how the 50,000 watt radio station could beam R&B music from Canada to Jamaica. “They were the first that had that kind of power, that kind of reach, that could be heard across half the country,” he said. “And basically you had these white DJs - John R., Hoss Allen and Gene Nobles - who were ignoring the color line.”

Gray argued this was progressive for its time. “Rhythm and blues music was still considered taboo by a lot of people, and the fact that this great music was coming out of Nashville had a huge impact,” he said.

WLAC’s radio play led to a demand for records, many of which were purchased from Nashville-based independent record labels. “As a result of WLAC you had sponsors like Ernie's Record Mart and Randy’s Record Shop. They were selling rhythm and blues records through mail order,” Gray said.

The story of Nashville’s R&B influence will continue to be told with the opening of the National Museum of African American Music, located just blocks away from the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum on Broadway.

“You know I’m not sure you can ask for a better location for this museum than 5th and Broadway,” says Henry Hicks, the institution’s president and CEO. “You come to Nashville. You come to the National Museum of African American Music. You get inspired. You get enthusiastic,” he said. “You’re reminded of that significant cultural and musical history that Nashville had such a big part of, you’ll also want to go over to Jefferson Street and see where it all happened.”

The museum is set to open in 2019. It will join Nashville’s business and political leaders, the Country Music Hall of Fame and The Jefferson Street Sound, which are all doing their part highlighting Jefferson Street on the historical record. Now it’s up to Nashville’s residents and tourists to keep those memories spinning.