There are 858 highway miles between Austin, TX and Nashville, TN. Musicians have been wearing deep ruts in the road in both directions for almost 50 years, fostering an artistically rich symbiotic relationship. Musicians have migrated back and forth. Songs and stories and ideas about art were exchanged, influencing American music and Southern culture. And that fascinating, colorful dichotomy is going on display at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum this week.

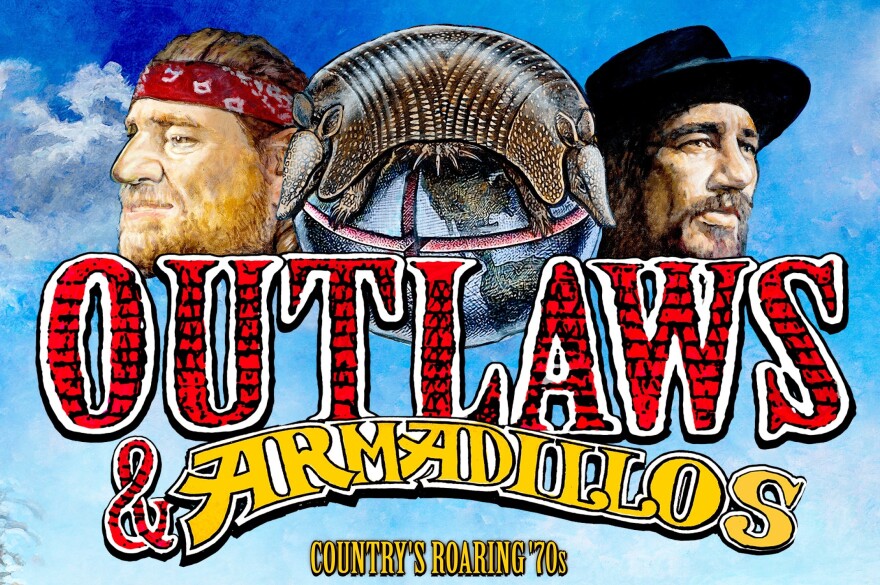

The exhibit Outlaws & Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s spotlights Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson on its poster, but it goes deep on a range of remarkable artists who defined an era: Billy Joe Shaver, Jessi Colter, Michael Martin Murphey, Kris Kristofferson, Jerry Jeff Walker, Guy Clark and Bobby Bare among them.

“What happened in the 1970s was musicians deciding they had to be in control of their creative selves,” says exhibit co-curator Peter Cooper. “It was really about Bobby Bare and Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson saying, 'Look I can do this. I don’t have to be told what to sing and who to sing it with.'"

Cooper says that while many think of the platinum-selling 1976 Wanted compilation album with previously released recordings by Nelson, Jennings, Colter and Tompall Glaser as the spark of the so-called Outlaw movement, in fact Bobby Bare’s 1972 album Lullabys, Legends and Lies was the catalyst. That’s because Chet Atkins was trying to lure Bare back to RCA Records and when Bare protested that he didn’t want the label’s history of overbearing supervision, Atkins granted him autonomy over his pickers and repertoire. In that instance, it was an entire album of songs by iconoclast Shel Silverstein, another major figure in the exhibit.

“And that opened the Pandora’s box,” Cooper said on a preview tour. “Then RCA could not tell Waylon Jennings that artists could not do that.” And thus did Jennings move off of Music Row proper and produce his own albums at Glaser’s studio on 19th Ave. S. known then and forever as Hillbilly Central.

That’s from the Nashville side of the story, where the country music industry lived. Austin was a hub for live performance, particularly at the legendary Armadillo World Headquarters, where Willie’s loose, jazz-influenced country music famously united demographically and socially diverse people - hippies and rednecks as they say - into one enthusiastic audience.

Unlike Nashville in the late 1960s, Austin welcomed influences and people from the West Coast psychedelic scene, so one of the most conspicuous elements of the city then and the exhibit now is a visual esthetic expressed mostly in show posters. A San Francisco transplant named Jim Franklin became what Sr. Creative Director Warren Denney called the godfather of the scene. Denney says Franklin conceived the armadillo as the symbol of the Austin counter-culture. He and a collective of artists who essentially lived at the Armadillo World Headquarters applied their fine hand at elaborate pen and ink drawings that gave the time its look and vibe.

“The scene in Austin was very much on par with San Francisco, LA, New York as far as the underground art scene went,” Denney told WMOT. “And the gig posters that were coming out of there were just phenomenal. The exhibition itself is so zoned in on the mash up between the counter-culture and the country culture and the social experimentation that was going on down there at the time, the artwork reflected all of that in such a real way there was no other place to go other than go track those guys down.”

The history covered in Outlaws & Armadillos only spans about eight years, but it’s packed with characters bent on doing things their own way, including Austin DJ Joe Gracey who spearheaded a “progressive country” format at Austin’s KOKE radio, Nashville’s Cowboy Jack Clement who brought whimsy to his songs and production and Hondo Crouch, the eccentric rancher who established a music scene in nearby Luckenbach, TX.

It’s a lot to take in but fans will have a while to do so. The exhibit is planned for a nearly three year run.